Cite as: Harrison, M., and Benner, S. A. (2022) “Mark Harrison and Steven Benner remark on NASA’s “Standards” White Paper. Does NASA’s drive for consensus make young scientists susceptible to being trampled by mastodons?”. Primordial Scoop, e20220525. https://doi.org/10.52400/DVGO6088

One strength of a civilization is found in its tools to store information in ways that allow the next generation of scientists to learn from mistakes made by their predecessors. This comes with a risk, of course. The young scientists might, instead, learn from the past only the biases of their predecessors, and therefore make the same mistakes.

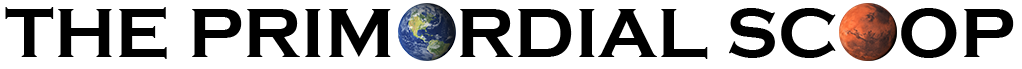

Fortunately, youth often have innate skepticism. This gives them a natural predilection to question, and therefore avoid, the views of their ancestors. The balance between “taking instruction” and “inclination to rebel” is delicate, perhaps honed by the evolution of humankind during the Ice Age. Then, DNA too inclined to rebel and accepting too little instruction, or too slavish to instruction and thus never rebelling, was lost to natural selection, being trampled and gored by mastodons that they encountered as they moved out of Africa.

The NASA-impaneled Community Workshop that explored “Biosignatures Standards of Evidence” to evaluate claims of life detection has been criticized for its favoring “instruction” over “rebellion”. For example, Carol Cleland noted on these pages how the White Paper Report from the Workshop misrepresents the lessons offered by the Viking 1976 exploration of the Martian surface.

Likewise, the recent report of phosphine in the atmosphere of Venus, correct or incorrect, prompted a remarkable set of “out of the box” discoveries about chemistry possible in concentrated sulfuric acid in the clouds above Venus. Had they been adopted by young scientists, the prescriptions in the White Paper would surely have prevented this work.

The mis-instruction in the Standards White Paper extended to work done on Earth to seek signatures of very ancient Terran life. The White Paper correctly noted that Bill Schopf in 1993 discovered in Australian sedimentary rocks structures that he interpreted as representing microbial taxa ~3.5 billion years old. The White Paper correctly notes the controversiality of this interpretation, as well as the ease with which ancient rocks are contaminated by modern organic molecules introduced during their collection and processing.

However, at least in our view, the White Paper draws the wrong conclusion, “the need for a community wide adoption of a standard set of criteria for assessing potential preserved biosignatures”.

We understand the cosmetic appeal of creating a community consensus for reporting evidence of life on early Earth, other Solar System bodies, and exoplanets. However, that word – consensus – comes highly charged, even when studying natural history on Earth, where the record can be explored with much less cost than on a relatively nearby world such as Mars.

This is particularly true where Deep Time on Earth is involved, due to the paucity of the rock record.

During our careers, we have seen the Earth and planetary communities prematurely coalesce around numerous concepts before their underlying mechanisms were well understood. These include, in no particular order:

• that the first half billion years of Earth history saw a desiccated, molten, lifeless planet;

• that a Mars-sized impactor formed Moon;

• that our Moon experienced a Late Heavy Bombardment ~3.9 billion years ago;

• that plate tectonics initiated 3 billion years ago.

All of the above concepts are today under serious challenge as a result of new thinking that was, in our view, forestalled by decades of conformity to various consensuses that were built upon weak evidentiary foundations. By not resisting the call to group think in these and other cases, we retarded progress.

How many young scientists would have been inspired to pursue alternate explanations for lunar formation, or the origin of continental crust, or the lunar bombardment history, had we not instructed them that these were solved problems? Or that a NASA committee had decided that questions were outside the “consensus” conformity and non-diversity that appears to be NASA’s touchstone today?

Any statement that there is one correct way of looking at a problem as poorly understood as the nature of life in the universe is more likely to obstruct its exploration than lubricate the process of discovery.

A second concern within the White Paper relates to the necessarily limited knowledge of its authors. This led to texts that are best described as “morality tales”.

Returning to Bill Schopf, an example comes from this paragraph:

“Claims of signs of life in the early rock record similarly illustrate the need for consistent criteria in defining biological origin, as well as the importance of contamination evaluation and the enhanced rigor enabled when multiple teams engage in assessment of claims of biosignature detection. In one example, Schopf (1993) described “microfossil-like objects”, which he interpreted as eleven different microbial taxa in a ~3.5 Ga sedimentary chert rock. These structures were reinterpreted by Brasier et al. (2002) as abiotic organic matter in a hydrothermal setting. The debate has continued for over 30 years, with Rouillard et al. (2021) noting that the criteria used for biological origin was inconsistent within the community, causing the fossil-like structures to sometimes be presented as evidence for biological activity, and other times as abiotic. This example underscores the need for community-wide adoption of a standard set of criteria for assessing potential preserved biosignatures.”

To the impartial reader, the paragraph sets up Schopf as the fall guy for the truth of Brasier et al., with a moral, that we need consensus criteria for evidence of life to avoid such false reports. But more recently, Schopf et al. (2018) examined those microfossils in situ and found a narrow range of δ13C values consistent with biologic activity that vary systematically between taxa. This appeared to corroborate their putative biogenicity. Further, correlations between δ13C compositions and morphological identification would seem to bolster confidence in their taxonomic assignments.

It unclear how any reporting criteria would have improved progress on this front. It does make clear how such criteria might have created climates, as chilly as the Ice Age, for funding and publication in the complex back and forth that characterizes real science as it actually is practiced.

We and others are left with the overarching impression that the White Paper is a kind of rearguard action to place a buffer between anticipated observations from planned NASA missions, or missions outside of NASA, and their dissemination.

If so, then this speaks more to the wisdom of funding missions that are unable to articulate how their observations will be evaluated in a life detection scheme than it does justify the need for a new groupthink. But regardless of the purpose of the White Paper, its impact will be to shift the balance away from the rebellion needed in astrobiology, where the concepts are scarcely formed even as the technology to explore is rapidly becoming more powerful.

And that will make the next generation of astrobiologists more likely to be trampled and gored by the alien mastodons that they soon might encounter as they move off of Earth.