Herein is a copy of the official White Paper submission to NASA-DARES 2025 Request for Information by Christopher Temby on behalf of the Agnostic Life Finding Association (ALFA)

Cite as: Temby, C., Spacek, J. (2025) “How to Search for Unambiguous Signs of Extant Life on Mars with NASA-DARES 2025.” Primordial Scoop, e20250311. https://doi.org/10.52400/MSAA8103

1. Recommendation and Introduction

1.1 Recommendation

NASA’s Science Mission Directorate (SMD) and Mars Exploration Program (MEP) are recommended by Agnostic Life Finding Association (ALFA) [1] to produce a focused investigation to seek unambiguous signs of extant life within the Martian subsurface ice, in this decade, as a Discovery-class mission or by deploying an astrobiology payload in concordance with planned water-mining operations on Mars [2-5]. This recommendation is the second in a series of White Paper submissions by the author to inform the development of NASA’s 2025 Decadal Astrobiology Research and Exploration Strategy (NASA-DARES 2025), and follows from the arguments made within the previous submission [6].

Origins, Worlds, and Life: A Decadal Strategy for Planetary Science and Astrobiology 2023-2032 (OWL) [7] recommends that the MEP’s “next priority medium-class mission” seek signs of extant life in the Martian subsurface, exemplified by the Mars Life Explorer (MLE) mission concept study [8]. Relevant to NASA-DARES 2025 RFI’s Response Topic 7, this recommendation highlights necessary improvements to the proposed mission concept and provides considerations for the Search for Life Science Analysis Group (SFL-SAG).

1.2 Introduction

The Martian subsurface is likely to be inhabited today, if life ever existed on Mars [1, 7-10]. However, a growing impetus to put humans on Mars [11, 12] gives NASA limited time to search for an extant Martian biosphere before human arrival. A search for life on Mars would provide tremendous benefit to NASA [6, 13] by 1) addressing the dwindling timeline for thorough astrobiological investigation on a pristine Mars, 2) addressing contradictions within planetary protection protocols, 3) informing risk assessments for all future missions to the Red Planet, and 4) informing the development of all future missions searching for life in the Solar System.

Consequently, OWL recommended that a mission to search for signs of extant life shall be MEP’s “next priority medium-class mission” [7]. While this recommendation should be welcomed by “extant Mars-life advocates,” a thorough analysis of the proposed MLE mission concept [8] calls into question NASA’s confidence in detecting unambiguous signs of extant life with a mission like MLE [14]. The biggest flaw of NASA’s Viking missions was the ambiguity inherent in their methods to search for life [15, 16]. NASA cannot afford to make the same mistake again.

2. The Proposed Mission to Search for Extant Life is Insufficient

2.1 Discussion on Unambiguous, High-Confidence Biosignatures

Any payload to search for extant life shall seek high-confidence biosignatures that “climb” the “Ladder of Life Detection” (Table 2, Neveu et al. 2018) [17]. The “Ladder of Life Detection“ consists of “rungs,” each representing a different category of biosignatures, where a lower rung represents a decrease in the strength of that particular biosignature to be evidence of life. It includes multiple extremely high-confidence biosignatures, such as evidence of “Growth and Reproduction” or “Metabolism.” In reality, these are unlikely to be confidently obtained by a payload searching for extant life because of uncertainties associated with Terran biases: mission planners cannot be certain they know how to adequately cultivate oligotrophic Martian organisms, nor shall they expect to keep them alive for observation. This is supported by the fact that a majority of environmental microbes on Earth are unable to be cultured [18]. Hence, to avoid the false negative due to our assumed inability to grow Martian life, we should seek the next highest-confidence biosignatures: “Molecules and Structures Conferring Function” [17]. Furthermore, if the conferred molecular function is “information inheritance”, one can infer the existence of Darwinian evolution, given the unlikelihood of finding large informational polymers that are not sustaining (and are not sustained through) an ongoing evolutionary process.

The biosignatures populating the rung below “Molecules and Structures Conferring Function” are designated as “Potential biomolecule components.” Examples of molecules or components herein include amino acids, fatty acids, nucleic acid oligomers, and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) [17]. Their ambiguity may result in a false positive.

2.2 MLE is Insufficient with Regard to High-Confidence Biosignatures

Several aspects of the proposed mission to seek signs of extant life in the Martian subsurface [8] are well-founded. However, MLE’s primary science objective falls short. What ‘organic molecules’ shall MLE seek? Are they sufficiently agnostic to provide a confident, unambiguous detection of alien life? The MLE Science Traceability Matrix (Table 1-2, Williams 2021) [8] provides answers: MLE’s target materials include “amino acids, fatty acids… PAHs… and polynucleotides.” As noted above, in Section 2.1, none of the organic molecules MLE will target are sufficient to provide an unambiguous interpretation that extant life has been detected. All of MLE’s target materials have a known abiotic production pathway [17].

The OWL-recommended payload proposed to conduct a search for extant life is unlikely to detect sufficiently unambiguous biosignatures from the Martian subsurface ice deposits [8]. Amy Williams, the MLE Science Champion stated in an interview, “I don’t even know… what it would take for me to say, ‘Yes, definitely [we have detected extant life with MLE’… NASA or commercial partners] might have to send another mission to further investigate,” [19]. Traditionally, this would be an adequate strategy: provide further geochemical context to prepare for the next discovery. However, given the limited time to search for life on a pristine Mars, and ongoing efforts to increase government efficiency, it is no longer the right strategy to invest 10+ years and $1.1 billion on a life-finding mission, knowing long before the spacecraft is built that another mission, with better capabilities, may need to be sent.

2.3 MLE’s Sensitivity is Limited by Its Sample Size and Operations

All instruments flown to Mars since Viking would struggle to detect extant life in dry regions of the Atacama Desert because of their limited detection sensitivity [14]. Martian conditions are even more hostile than the Atacama Desert and likely host lower population densities (<100 cells per ml). With this perspective, the proposed MLE mission concept is insufficiently sensitive. It is only designed to drill a single, two-meter hole, to collect and characterize a few milliliters of ice [8]. The low-resource environment on Mars suggests that a tentative Martian biosphere might be physically completely missed by MLE if population densities are 100 cells per ml or less. Further, because of the relatively small sample size, and lack of preconcentration, the proposed tools onboard MLE would not be sensitive enough to detect alien life, even if the population densities were as “high” as those in the arid Mars analog environments discussed above [14].

Meanwhile, plans to enable crewed missions to Mars [4, 5] require large-scale in-situ resource utilization (ISRU) operations [3] to mine hundreds of tons of water. These large-scale water mining operations shall be considered the largest astrobiological sample ever collected and NASA shall leverage these operations to provide orders-of-magnitude larger sample sizes to enable a sufficiently robust search for extant life on Mars [2]. In summary, any payload seeking extant life on Mars must utilize larger sample collection efforts and seek higher-confidence biosignatures to produce the extraordinary evidence required to satisfy the extraordinary claims of discovering alien life. Even larger samples are needed to study this life.

3. How to Unambiguously Search for Extant Life

3.1 Enhancing the Proposed Mission Concept

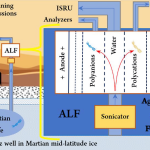

If NASA, through NASA-DARES 2025, is serious about searching for alien life, enhancements must be made to enable an unambiguous detection. Given that the proposed mission concept is insufficient to confidently detect alien life, how could NASA enhance the strategy to search for extant life? First, as discussed above, in Section 2.3, NASA shall leverage large-scale ISRU operations to acquire unprecedentedly large sample sizes, whereby preconcentration technologies can provide similarly unprecedented sensitivity [2].

Therefore, if preconcentration technologies are able to provide unprecedented sensitivity for life detection measurements, what biosignatures shall NASA seek to enable an unambiguous detection of life? Conveniently, we only need to continue reading the MLE mission concept study: “The baseline [proposal] does not carry… [technologies to enable] nucleobase-specific sequencing to further interrogate any life found… these technologies are currently lower Technology Readiness Level (TRL), but a future proposer could consider such enhancements,” [8]. This recommendation, to conduct nucleobase-specific sequencing, will require technologies to conduct in-situ analyses of “polymers that support information storage and transfer,” [17]. Furthermore, the Polyelectrolyte Theory of the Gene [20, 21] describes how and why these informational biopolymers are required to enable Darwinian evolution. Therefore, detection of polyelectrolyte informational biopolymers would be sufficient to provide a confident, unambiguous detection of life. Hence, we hereby (1) propose that such technology developments, to enable the extraterrestrial detection of polyelectrolyte informational biopolymers, must be prioritized by NASA-DARES 2025 to ensure that all future payloads searching for extant life are equipped to seek unambiguous target materials and (2) detail several key metrics that SFL-SAG shall consider in their quest to identify proper target materials and instruments to enable an unambiguous search for alien life.

3.2 For the SFL-SAG to Consider: A Search for Extant Life Shall…

A search for extant life shall investigate the Martian near-subsurface ice, brine, and/or water, and characterize the geochemical context of astrobiological samples to inform observations. The instruments conducting analyses must (1) provide measurements with sufficiently high sensitivity and (2) analyze sufficiently large sample volumes to confidently determine whether or not Mars hosts an active biosphere before human arrival. By assuming there exists (a) 1 femtogram of genetic material per alien cell, (b) 10 cells/ml in Martian ice, (c) 10% extraction/concentration efficiency of genetic material, and (d) a minimum required sample size of 10 nanograms to detect and characterize genetic material, the assumed sample size required to confidently detect alien life is 1,000 liters. These are conservative estimates, meaning that highly efficient preconcentration techniques, or a more densely populated biosphere, would enable detection with less sample. Nonetheless, plans require mining 100s of tons [2-5] (note: 1 metric ton of water is equivalent to 1,000 liters).

While an absence of evidence is not evidence of absence, a mission searching for life that finds no evidence of life can still yield a result with confidence limits. Confidence in a “no life” result shall arise through measurements with sufficient orthogonality and high sensitivity, on sufficiently large samples, to establish the lowest possible limit of uncertainty. On the other hand, if detected, the predetermined biosignatures must be unambiguous enough to provide confidence in declaring the discovery of alien life.

Furthermore, given the shortened timeline to assess a Martian biosphere, it is insufficient to merely provide a “life” or “no life” result (e.g. Labeled Release [15]). Therefore, the payload shall (1) begin studying the extant life in order to inform risks related to planetary protection and crewed missions, (2) enable the observation of a ‘whole ecosystem,’ as identified by NASA’s Space Technology Mission Directorate’s (STMD) 2024 Civil Space Shortfall ID:1601 [22], and shall (3) enable the detection and monitoring of forward contamination to (a) avoid false positives, (b) attenuate the background noise to avoid false negatives, and (c) measure forward contamination levels on Mars before and after human arrival (Shortfall ID:1590 [22]).

This recommendation is the second in a series of White Paper submissions by the author [6]. The third submission will include a discussion of the technologies that shall be identified by NASA’s Astrobiology Program, and developed by NASA’s STMD, to actualize the recommendations herein to search for unambiguous signs of extant life on Mars before human arrival.

References

[1] ALFA Mars. “Is there life on Mars?” www.alfamars.org

[2] Špaček, J., & Benner, S. A. (2022). “Agnostic life finder (ALF) for large-scale screening of martian life during in situ refueling.” Astrobio, 22(10), doi.org/10.1089/ast.2021.0070

[3] Mellerowicz, B., et al. (2022). “Redwater: Water Mining System for Mars.” New Space, 10(2), 166–186. doi.org/10.1089/space.2021.0057

[4] Heldmann, J. L., et al. (2022). “Mission architecture using the spacex starship vehicle to enable a sustained human presence on Mars.” New Space, doi.org/10.1089/space.2020.0058

[5] Musk, E. (2017). “Making Humans a Multi-Planetary Species.” New Space, 5(2), 46–61. https://doi.org/10.1089/space.2017.29009.emu

[6] Temby, C. (2025) “Prioritize the Search for Extant Life on Mars with NASA-DARES 2025.” Primordial Scoop, e20250210. https://doi.org/10.52400/OJTV9012

[7] National Academies (2023). “Origins, Worlds, and Life: A Decadal Strategy for Planetary Science and Astrobiology 2023-2032.” Natl. Acad. Press. doi.org/10.17226/26522.

[8] Williams, A. (2021). “Mars Life Explorer Mission Concept Study.” NASA.

[9] Carrier, B.L., et al. (2020). “Mars Extant Life: What’s Next? Carlsbad Conference Report.” Astrobiology, vol. 20, no. 6, 1, pp. 785–814, https://doi.org/10.1089/ast.2020.2237.

[10] Cabrol, N.A. “Tracing a modern biosphere on Mars.” Nat Astron 5, 210–212 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41550-021-01327-x

[11] Reuters.com (2024). “SpaceX Plans to Send Five Uncrewed Starships to Mars in Two Years, Musk Says.” Reuters, 22 Sept. 2024.

[12] Rogers, J. (2024). “China Unveils Mars Plan in Bid to Send Humans by 2033 Amid ‘Space War’ Fears.” The US Sun. 6 Sept. 2024

[13] Stoker, C., et al. (2021). “We should search for extant life on Mars in this decade.” Bulletin of the AAS, 53(4). https://doi.org/10.3847/25c2cfeb.36ef5e33

[14] Azua-Bustos, A., et al. (2023) “Dark microbiome and extremely low organics in Atacama fossil delta unveil Mars life detection limits.” Nat Commun doi.org/10.1038/s41467-023-36172-1

[15] Klein, H. P. (1978). “The Viking Biological Experiments on Mars.” Icarus, 34(3), 666–674. https://doi.org/10.1016/0019-1035(78)90053-2

[16] Christopher P. McKay, Richard C. Quinn, Carol R. Stoker. (2025) “The Viking Biology Experiments on Mars Revisited” Icarus, vol. 431. doi.org/10.1016/j.icarus.2025.116466

[17] Neveu, M., et al. (2018). “The Ladder of Life Detection.” Astrobiology, vol. 18, no. 11, Nov. 2018, pp. 1375–1402, doi.org/10.1089/ast.2017.1773.

[18] Liu, S., et al. “Opportunities and challenges of using metagenomic data to bring uncultured microbes into cultivation.” Microbiome 10, 76 (2022). doi.org/10.1186/s40168-022-01272-5

[19] Al-Ahmed, S. (2023, Aug. 9). “Mars Life Explorer: The search for extant life on the red planet.” Planetary Radio, www.planetary.org/planetary-radio/2023-mars-life-explorer.

[20] Benner, S. A., & Hutter, D. (2002). “Phosphates, DNA, and the search for Nonterrean Life: A second generation model for genetic molecules.” Bio.o Chem, doi.org/10.1006/bioo.2001.1232

[21] Benner, S. A. (2017). “Detecting Darwinism from Molecules in the Enceladus Plumes, Jupiter’s Moons, and Other Planetary Water Lagoons.” Astrobio., doi.org/10.1089/ast.2016.1611

[22] NASA. (2024). “NASA Releases First Integrated Ranking of Civil Space Challenges.” NASA. www.nasa.gov/general/nasa-releases-first-integrated-ranking-of-civil-space-challenges