Herein is a copy of the official White Paper submission to NASA-DARES 2025 Request for Information by the Agnostic Life Finding Association (ALFA)

Cite as: Temby, C., Spacek, J., Benner, S. A. (2025) “Searching for Unambiguous Signs of Extant Life on Mars with the Agnostic Life Finder (ALF).” Primordial Scoop, e20250317. https://doi.org/10.52400/SCRL7105

1. Recommendation and Introduction

1.1 Recommendation

NASA’s Science Mission Directorate (SMD) and Mars Exploration Program (MEP) are recommended by the Agnostic Life Finding Association (ALFA) [1] to produce a focused investigation to seek unambiguous signs of extant life within the Martian subsurface ice, in this decade, by deploying the Agnostic Life Finder (ALF) [2] in concordance with planned water-mining operations on Mars [3-6]. This recommendation is the third in a series of White Paper submissions by the author to inform the development of NASA’s 2025 Decadal Astrobiology Research and Exploration Strategy (NASA-DARES 2025), and follows from the arguments made within the previous submission [7].

Origins, Worlds, and Life: A Decadal Strategy for Planetary Science and Astrobiology 2023-2032 (OWL) [8] recommends that the MEP’s “next priority medium-class mission” seek signs of extant life in the Martian subsurface, exemplified by the Mars Life Explorer (MLE) mission concept study [9]. Relevant to NASA-DARES 2025 RFI’s Response Topic 2, this recommendation highlights emerging technologies capable of detecting unambiguous signs of extant life, having the potential to transform the field of astrobiology.

1.2 Introduction

As discussed in the previous submission [7], the OWL-recommended payload proposed to conduct a search for extant life on Mars is unlikely to detect sufficiently unambiguous biosignatures [9]. Now, with limited time to search for life on a pristine Mars before crewed missions, it is not the right strategy to invest in an ambiguous life-finding mission, knowing another mission may need to be sent, with better capabilities, to answer the same question.

Given the proposed concept [9] is insufficient [7], how could NASA enhance the strategy to search for extant life? First, an astrobiological payload’s sample size must be large enough to adequately assess an extremely sparse biosphere, accounting for the analytical instrument sensitivity, expected population densities, and detection confidence requirements. Second, the detection must be unambiguous. Quoting the MLE mission concept study, “the [payload shall] carry… [technologies to enable] nucleobase-specific sequencing to further interrogate any life… these technologies are currently lower Technology Readiness Level (TRL), but a future proposer could consider such enhancements,” [9]. Thus, we propose such enhancements.

In summary, to provide sufficient confidence in either a positive or negative detection of sparse alien life on Mars, the detection instrumentation must screen samples upwards of 1,000 liters and seek high confidence biosignatures[7].

2. The Agnostic Life Finder (ALF) Technology

The recommendation to conduct “nucleobase-specific sequencing” requires technologies to conduct in-situ analyses of “polymers that support information storage and transfer,” as described in the “Ladder of Life Detection” [10]. To develop this capability, ALF was selected by NASA’s Innovative Advanced Concepts (NIAC) Program, and was advanced to TRL 4 under Phase I [11]. The team [1] is pursuing NIAC Phase II support to develop a TRL 6 ALF system.

2.1 ALF’s Design and Subsystems

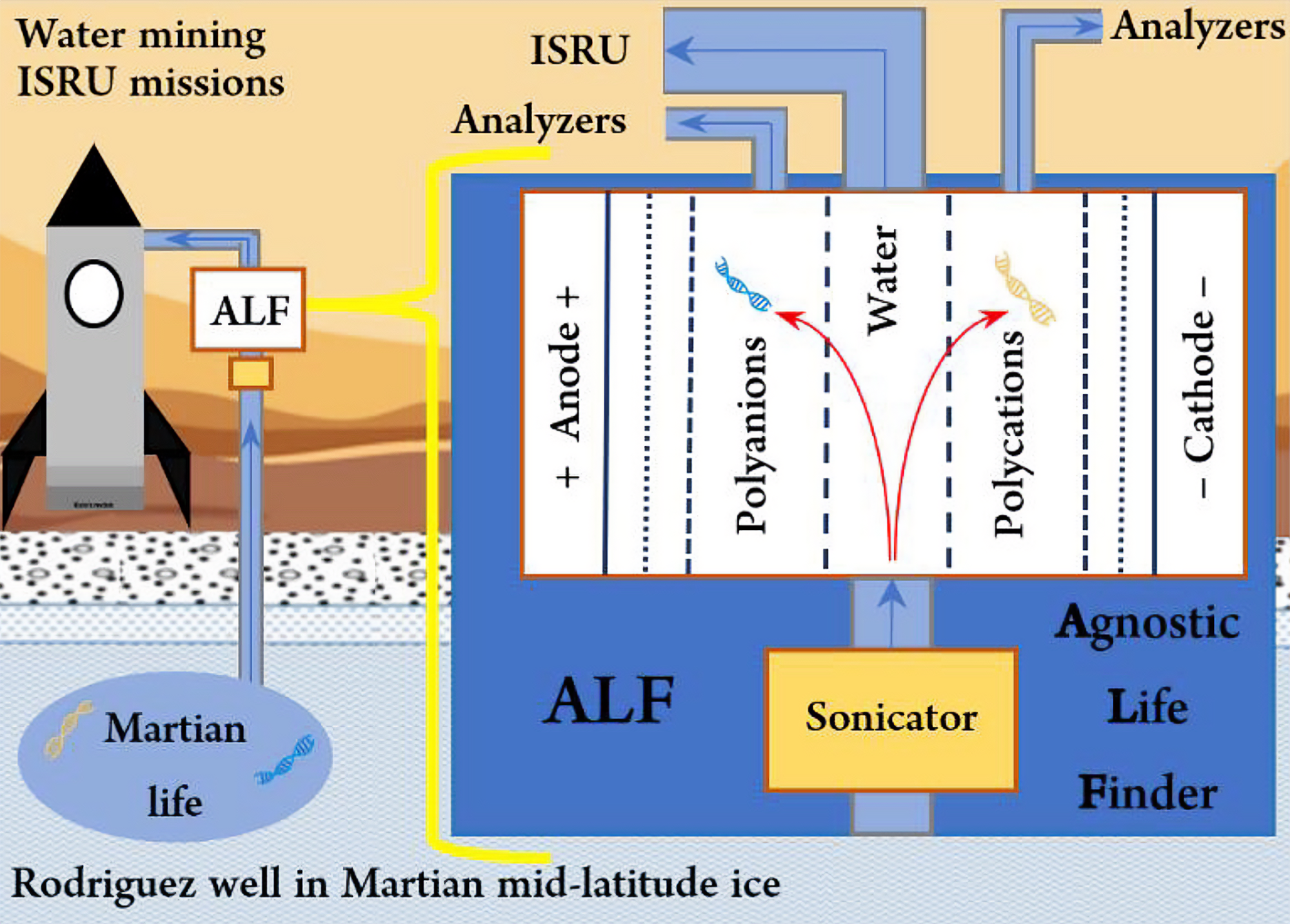

Plans to enable crewed missions to Mars [3-6] require large-scale in-situ resource utilization (ISRU) operations to mine hundreds of tons of water. Accordingly, the Agnostic Life Finder (ALF) [2] is designed to isolate, desalt, and concentrate sparse polyelectrolytes from large volumes of water. To enable this, ALF uses continuous electrodialysis with porous membranes to isolate and concentrate polyelectrolytes (DNA, RNA, or alien informational biopolymers) from water, based on size and charge. Polyelectrolytes move in an electric field, and are bigger than inorganic electrolytes (salts), allowing ALF to concentrate them by electromigration in water through size-exclusionary membranes. ALF can achieve an arbitrarily low limit of detection for informational biopolymers, where the sensitivity is limited only by the sample volume that ALF inspects. Polyelectrolytes will then be analyzed. Known genetic material recovered by ALF will be sequenced by biological nanopore; unknown polyelectrolytes will be analyzed by solid-state nanopores and/or fragmentation mass spectrometry to illuminate Schrödinger regularity in heteropolymers built from a small set of size-regular units [12, 13].

The ALF system comprises several subsystems: (1) a preconcentrator, (2) a desalting unit, (3) a sonicator, (4) the ALF stack, (5) a polyelectrolyte concentrator, and (6) analyzers. The system is capable of inspecting extremely large volumes of water to analyze polyelectrolytes. For example, the preconcentrator can input ~100,000 L of water, outputting ~10,000 L of concentrated particulate stream. The ALF Stack inputs the ~10,000 L and outputs ~100 L of purified polyelectrolytes. The polyelectrolyte concentrator inputs ~100 L of purified polyelectrolytes and outputs ~100 ml of highly concentrated polyelectrolytes for analysis. Therefore, the ALF system improves the sensitivity of polyelectrolyte analysis ~1,000,000 fold on Mars. Samples of concentrated polyelectrolyte can also be stored for return to Earth. The high degree of the sample preconcentration is not uncalled for:

By assuming (a) 1 femtogram of genetic material per alien cell, (b) 10 cells/ml in Martian ice, (c) 10% extraction/concentration efficiency of genetic material, and (d) a minimum required sample size of 10 nanograms to detect and characterize genetic material using solid state nanopore, the assumed sample size required to confidently detect alien life is 1,000 liters. ALF’s concentration efficiency will likely be higher, enabling detection with less sample. Nonetheless, plans to enable crewed missions [3-6] require mining 100s of tons of water. Given that the analyzed ice will contain traces of aeolian deposits, ALF enables the observation of the “whole ecosystem” and offers a cost-effective “sensing/monitoring” solution to address planetary protection shortfalls (Space Technology Mission Directorate’s (STMD) Shortfall IDs 1601 and 1590 [14]) and knowledge gaps [15].

2.2 ALF Manages the Concerns Raised about Polyelectrolyte Detection

The “Ladder of Life Detection” paper by Neveu et al (2018) [10], authored by NASA HQ staff, endorses a polyelectrolyte polymer as a worthy biosignature for a mission searching for Mars life. However, concerns are raised that polyelectrolyte “detectability may be hampered by dilution” and their “survivability… is limited by hydrolysis” [10]. The former concern is easily solved by utilizing electrodialysis to concentrate polyelectrolytes from a dilute solution. Addressing the latter concern, the long-term instability of polyelectrolytes in water is actually a benefit when seeking extant life: if polyelectrolytes are detected, their long-term instability means that something must be replenishing them. Thus, since biology is required to sustain large polyelectrolytes, their detection would be sufficient to provide an unambiguous detection.

3. Applying the Agnostic Life Finder (ALF)

Next we discuss how, where, and why the instrument shall be applied, in order to persuade NASA, through NASA-DARES 2025, to develop and fly this particular life detection strategy.

3.1 Large-Scale In-Situ Resource Utilization for Human Missions

To enable crewed landings, large quantities of water will be extracted for propellant manufacturing and human consumables [3-6]. These operations will target the mid-latitude subsurface ice, increasing in scale to meet increasing ISRU needs. Given its abundance and accessibility from the surface, this ice can be remotely extracted using Rodriguez Wells. NASA already pays to develop such a concept: Honeybee Robotics’ RedWater RodWell System [4]. These large-scale water mining operations shall be considered the largest astrobiological sample ever collected [2]. To anticipate and align SMD, STMD, Exploration Science Systems Integration Office (ESSIO), and Exploration Systems Development Mission Directorate (ESDMD) objectives, NASA shall leverage these operations to provide unprecedentedly large sample sizes, whereby ALF can provide similarly unprecedented sensitivity, to enable a robust search for life on Mars.

Thus, “how to apply ALF?”: ALF shall be applied as a “low-cost add-on” life detection instrument to missions testing and operating robotic water mining equipment.

3.2 The Martian Mid-Latitude “Lasagna” Ice is a Life-Supporting Resource

Just as the mid-latitude ice on Mars will be a life-supporting resource for human visitors, it may also be for living Martians. The top layers of Martian mid-latitude subsurface ice, now under less than 1 m of soil at 40 °N, are geologically young, deposited as ice-dust “lasagna” layers during recurring high obliquity periods (~100,000 yr cycles) [15-17]. Cyclic obliquity, dust storms, aeolian transport, and northward-flowing subsurface aquifers driven by high southern elevations facilitate planetary-scale spreading of surface material [15-18]. Over geologic timescales, material is moved around the entire planet, including any biological material present [18, 19]. This is analogous to Earth’s glacial ice, into which viable microscopic organisms from around the planet are deposited, where they remain for millions of years [20]. The ice to be mined during ISRU operations will contain any Martian microorganisms that were present during that ice’s deposition. This eliminates any need to target specific astrobiological locales, or oases.

Thus, “where do we deploy ALF?”: The mid-latitude subsurface “lasagna” ice enables NASA to screen the entire Martian surface for extant life, even if it proliferates only in a few “oasis” regions. Thus ALF remains agnostic to the global ecological distribution of Martian life.

3.3 Polyelectrolyte Theory of the Gene Changed the Biosignature Narrative

The biggest flaw of NASA’s Viking missions was the ambiguity inherent in their methods to search for life [21, 22]. NASA cannot afford to make the same mistake again, and yet none of the proposed target materials MLE seeks are sufficient to provide an unambiguous interpretation [7]. The Polyelectrolyte Theory of the Gene (PETOG) [23-25] enables missions searching for extant life to avoid ambiguous biosignatures. PETOG posits that the informational needs of Darwinian evolution universally require a linear polymer that has just two (and no other) molecular features: (a) A repeating, backbone charge (informational genetic biopolymers must be polyelectrolytes); (b) A controlled number of size-/shape-interchangeable informational units.

PETOG has both theoretical and empirical support. Synthetic biologists have made and tested “alien” genetic molecules that differ in structure from DNA and RNA [24-28]. Biopolymeric alternatives to DNA or RNA that have these two features do support Darwinian evolution in the lab [24-26]. Candidates that lack either of these features do not [27, 28]. Additionally, size-/shape- interchangeable informational units allow the information content of an informational biopolymer to change (ie. mutate) while retaining the Schrödinger “aperiodic crystal structure” needed for faithful replication. In other words, repeating charges allow a biopolymer’s information content to change, while still retaining the physical properties needed for molecular information replication.

Thus, “why ALF?”: ALF provides an unambiguous detection method to screen the entire surface for presence of extant life and avoids false positive and false negative results by seeking molecules necessary for Darwinian evolution.

4. Call to Action — ALFA’s Mission

For all of these reasons, (1) ALFA proposes that technology developments to enable the extraterrestrial detection and sequencing of polyelectrolyte informational biopolymers be prioritized by NASA-DARES 2025, ensuring that all future payloads searching for extant life are equipped to seek unambiguous target materials; (2) ALFA highlights the Agnostic Life Finder (ALF) [2] as an emerging technology which greatly advances the state of the art, with high potential to transform the field of astrobiology; and (3) ALFA advises NASA to apply the life detection strategy herein prior to human arrival on Mars.

References

[1] ALFA Mars. “Is there life on Mars?” www.alfamars.org

[2] Špaček, J., & Benner, S. A. (2022). “Agnostic Life Finder (ALF) for large-scale screening of Martian life during in-situ refueling.” Astrobiology. 22(10), doi.org/10.1089/ast.2021.0070

[3] Heldmann, J. L., et al. (2022). “Mission architecture using the spacex starship vehicle to enable a sustained human presence on Mars.” New Space, doi.org/10.1089/space.2020.0058

[4] Mellerowicz, B., et al. (2022). “Redwater: Water Mining System for Mars.” New Space.

[5] Musk, E. (2017). “Making Humans a Multi-Planetary Species.” New Space, 5(2), 46–61.

[6] Starr, S. O., Muscatello, A. C., (2020). “Mars in-situ resource utilization: a review.” Planetary and Space Science. vol. 182. doi.org/10.1016/j.pss.2019.104824

[7] Temby, C., Špaček, J. (2025) “How to Search for Unambiguous Signs of Extant Life on Mars with NASA-DARES 2025.” Primordial Scoop, e20250311. https://doi.org/10.52400/MSAA8103

[8] National Academies (2023). “Origins, Worlds, and Life: A Decadal Strategy for Planetary Science and Astrobiology 2023-2032.” Natl. Acad. Press. doi.org/10.17226/26522.

[9] Williams, A. (2021). “Mars Life Explorer Mission Concept Study.” NASA.

[10] Neveu, M., et al. (2018). “The Ladder of Life Detection.” doi.org/10.1089/ast.2017.1773

[11] NASA. (2024). “Add-on to large-scale water mining operations on Mars to screen for introduced and alien life.” www.nasa.gov/general/large-scale-water-mining-operations-on-mars

[12] Schrödinger, E. (1944). “What Is Life: The Physical Aspect of the Living Cell.” Camb.U.P.

[13] Faulstich, K., et al. (1997). “A Sequencing Method for RNA Oligonucleotides based on Mass Spectrometry.” Analytical Chemistry, https://doi.org/10.1021/ac961186g

[14] NASA. (2024). “NASA Releases First Integrated Ranking of Civil Space Challenges.” NASA. www.nasa.gov/general/nasa-releases-first-integrated-ranking-of-civil-space-challenges

[15] Spry, J. A., et al. (2024). “Planetary Protection Knowledge Gap Closure Enabling Crewed Missions to Mars.” Astrobiology, 24(3), 230–274. https://doi.org/10.1089/ast.2023.0092

[16] Špaček, J. (2021) “Cooking Lasagna Glaciers on Mars”. Primordial Scoop, 2021, e0120.

[17] Madeleine, J. B., et al. (2014). “Recent ice ages on Mars: The role of radiatively active clouds and Cloud Microphysics.” Geophysical Research Letters, doi.org/10.1002/2014gl059861

[18] Cabrol, N.A., (2021). “Tracing a Modern Biosphere on Mars.” Nature Astronomy.

[19] van Heereveld, L., et al. (2016). “Assessment of the Forward Contamination Risk of Mars by Clean Room Isolates from Space-Craft Assembly facilities through Aeolian Transport – A Model Study.” Origins of Life and Evolution of Biospheres, vol. 47(no. 2): p. 203–214.

[20] Bidle, K. D., et al. (2007). “Fossil genes and microbes in the oldest ice on Earth.” PNAS, 104(33), 13455–13460. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0702196104

[21] Klein, H. P. (1978). “The Viking Biological Experiments on Mars.” Icarus, 34(3), 666–674.

[22] McKay, C.P., Quinn, R. C., Stoker, C. (2025) “The Viking Biology Experiments on Mars Revisited” Icarus, vol. 431. doi.org/10.1016/j.icarus.2025.116466

[23] Benner, S. A. (2017). “Detecting Darwinism from Molecules in the Enceladus Plumes, Jupiter’s Moons, and Other Planetary Water Lagoons.” Astrobio., doi.org/10.1089/ast.2016.1611

[24] Benner, S. A., Hutter, D. (2002) “Phosphates, DNA, and the search for Nonterrean Life: A second generation model for genetic molecules.” BioOrg Chem, doi.org/10.1006/bioo.2001.1232

[25] Benner, S. A., et al. (2016). “Alternative Watson–Crick Synthetic Genetic Systems.” Cold Spring Harbor Perspectives in Biology, 8(11). doi.org/10.1101/cshperspect.a023770

[26] Hoshika, S., et al. (2018). “‘Skinny’ and ‘Fat’ DNA: Two new double helices.” Journal of the American Chemical Society, 140(37), 11655–11660. https://doi.org/10.1021/jacs.8b05042

[27] Schneider, K. C., & Benner, S. A. (1990). “Building blocks for oligonucleotide analogs with dimethylene-sulfide, -sulfoxide, and -sulfone groups replacing Phosphodiester linkages.” Tetrahedron Letters, 31(3), 335–338. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0040-4039(00)94548-9

[28] Miller, P. S., et al. (1981). “Biochemical and biological effects of nonionic nucleic acid methylphosphonates.” Biochemistry, 20(7), 1874–1880. doi.org/10.1021/bi00510a024